Want better sessions? Start with your kite

Look, I'll be honest, when I first started kitesurfing, I had no clue what made one kite different from another. They were all just... colorful flying things that dragged me around. And you know what? That was totally fine for a while.

This guide is everything I wish someone had told me when I started getting serious about kites. It's long, like, grab-a-coffee long, but you don't need to read it all at once. Jump to whatever section you're curious about, or read it front to back if you're a nerd like me.

1. What's actually inside my kite?

Ever wondered what you're actually pumping up when you're huffing and puffing on the beach? Let's crack open a kite and see what makes it tick.

1.1 Inflatable (LEI) kites

When most people picture kitesurfing, they're thinking of LEI kites (Leading Edge Inflatable). These are the ones you pump up before hitting the water, and honestly, they're kind of brilliant.

Here's what's going on inside:

The whole structure is based on tubes of air. You've got the leading edge (the big tube that forms the front arc of the kite) and struts (the ribs that run from front to back, giving the kite its shape). Inside each of these is a TPU bladder, basically a balloon that you inflate until it's firm. Not basketball-hard, but firm enough that the kite holds its shape.

The airframe, that's the fabric sleeve around the bladders, is usually made of Dacron, which is tough stuff. Think of it as the kite's skeleton. Then you've got the canopy, made from ripstop nylon or polyester, cut and stitched into a curved airfoil shape. Those panels are sewn together with beefy seams (often triple-stitched) because the last thing you want is your kite unzipping mid-session.

Now, those spidery lines you see on the leading edge? Those are bridles. They distribute the force across the kite and help it hold its shape when you're riding. Some kites have pulleys in the bridle system to adjust the angle of attack, fancy stuff.

The beautiful thing about inflatables? They float. Drop one in the water and it bobs there like a patient friend waiting for you to get your act together. Trust me, this feature alone has saved countless sessions.

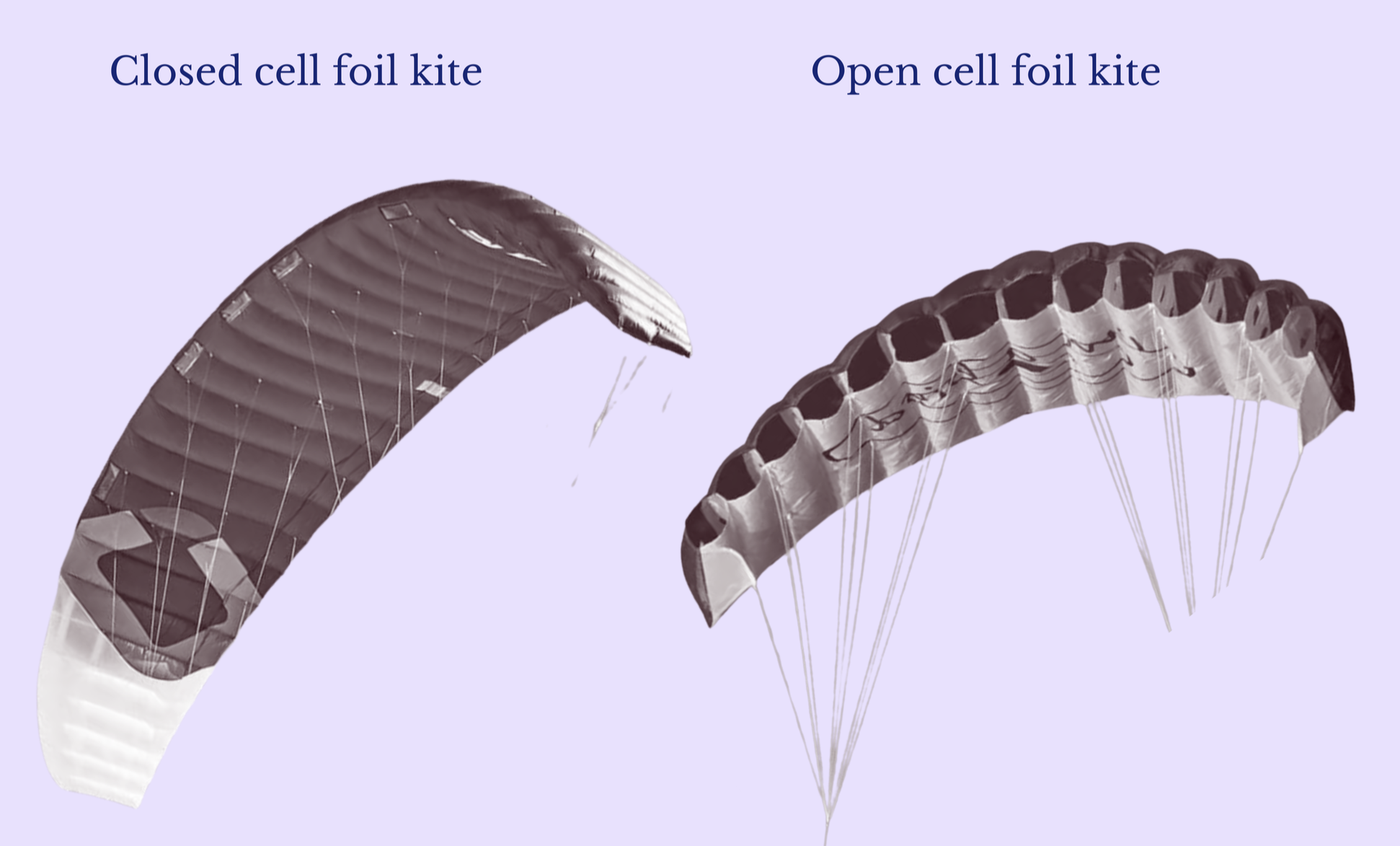

1.2 Foil kites

Foil kites are a whole different beast. No pump required, they inflate themselves with wind. Sounds perfect, right? Well, yes and no.

Here's how they work:

Picture a parachute that's been to engineering school. Foil kites have two layers of canopy fabric that form dozens of internal air cells. Wind rushes in through mesh-covered openings in the leading edge, filling up these cells and giving the kite its shape.

Inside, you've got fabric ribs and internal bridles acting as the skeleton, no rigid parts at all, just incredibly clever string and cloth engineering. Because there's no inflatable structure, foils are super light and pack down small. Like, fit-in-your-backpack small.

The water problem:

Here's where it gets tricky. Open-cell foil kites (the most common type) have those openings to let wind in, right? Well, they also let water in. Drop an open-cell foil in the water and it becomes waterlogged spaghetti pretty quickly. Not ideal for kitesurfing.

Closed-cell foils tried to solve this by adding one-way valves to hold air in, so theoretically you can relaunch them from water. Some even have internal drain systems. But honestly? Foils are still fussy compared to inflatables. You need steady wind to fill the cells properly, and if you tangle that massive bridle system, you're in for a bad time.

If an inflatable kite is a sturdy 4x4 truck, a foil kite is a race car. Lighter, more efficient, but you don't exactly want to crash it into the waves repeatedly.

1.3 The visual breakdown

Inflatable LEI kite

Bladders (the balloons inside).

Airframe (Dacron sleeve, the skeleton).

Canopy (ripstop fabric, the skin).

Struts (the ribs that hold shape).

Bridles (the steering system).

Result: Robust, floats, a bit heavy.

Foil kite

Double-layer canopy forming air cells.

Fabric ribs (internal structure).

Complex bridle web (like a spider's been busy).

Mesh intakes (wind goes in).

Result: Super light, packs small, hates water.

Both are doing the same job, generating power to pull you across water, they just take very different approaches to get there.

2. Materials: Should I care what my kite is made of?

For the first year or two, I didn't think much about kite materials. A kite was a kite, right? Then I borrowed a friend's high-end kite for a session and... wow. Suddenly my trusty kite felt like I'd been flying a bedsheet attached to tent poles.

So yeah, materials matter.

2.1 The standard stuff

Most kites you'll see (and probably ride) use standard materials that have been proven over years of getting absolutely thrashed by wind, water, and sun.

Canopy: Ripstop polyester or nylon. The "ripstop" part means there are reinforcement threads woven in, so if you tear it, the rip won't run wild across the whole kite. It's durable, handles UV pretty well, and holds its shape under tension.

Leading edge & struts: Dacron, which is a heavy-duty polyester weave. This stuff is bombproof. It's the reason your kite survives crash landings on the beach, getting dragged through sand, and those moments when you really should have depowered but didn't.

The pros: Proven, durable, affordable (relatively speaking because kites are never cheap, let's be real), and every kite shop knows how to repair this stuff.

The cons: It's heavy. If you've ever carried a 17m kite across a beach, you've felt the Dacron workout. Also, it's made from petroleum, so not exactly winning any environmental awards.

My take: This is what most riders use, myself included for most of my quiver. It works. It lasts. And when you're learning or progressing, you don't need to drop extra cash on exotic materials. Save that money for more sessions.

2.2 The fancy stuff: Aluula & friends

Then there's the space-age stuff that makes gear nerds (guilty) get all excited.

Enter Aluula.

Aluula is a composite material that's about 50% lighter than standard Dacron and supposedly 8 times stronger than steel relative to its weight. Yeah, someone actually compared it to steel, which seems excessive but makes for good marketing.

How it changes things:

When you replace the Dacron frame with Aluula, the kite's weight drops significantly, some kites shed half their weight. And that's not just about easier setup; it changes how the kite flies. Lighter kites:

Get up in lighter winds (better low-end).

Feel more responsive in your hands.

Are easier to relaunch (less weight to flip over).

Stay stable at the top end better.

The secret sauce is UHMWPE fiber (ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene, say that three times fast) fused with film at a molecular level. No heavy glues. And it's 100% polyethylene, which theoretically makes it recyclable.

Other fancy materials:

Brands have their own magic sauces: Duotone's Penta TX, various "lighter Dacron" blends with names like Ho'okipa or whatever the marketing team dreamed up that quarter. They all aim to shave grams while maintaining strength.

There's also ongoing R&D into sustainable materials like recycled polyester yarns, bio-based resins. Duotone's Concept Blue project, for instance, aims to cut water use by about 46% and CO2 by around 12% in production.

The reality check:

Aluula and similar high-tech materials are expensive. Like, really expensive. We're talking high-tech tax that can add €500-1000+ to a kite's price. And because they're relatively new, we're still learning how they age. Do they last as long as battle-tested Dacron? Time will tell.

2.3 The eco question

Let's be real for a second: most kites aren't great for the planet. They're made from petroleum-based materials, shipped globally, and when they die, they're basically unrecyclable mixed-material nightmares.

Some brands are trying to do better with using recycled materials, reducing production waste, and designing for longevity. But we're still pretty far from truly sustainable kites.

What matters to me personally: I try to take care of my gear so it lasts longer. Rinse with fresh water, store properly, repair instead of replace when possible. It's not perfect, but it's something. And when I do buy new gear, I'm starting to pay more attention to which brands are at least trying to reduce their impact.

2.4 When material actually matters

Here's the thing: for most recreational riding, standard materials are totally fine. But there are situations where upgrading makes a real difference:

Light wind days: A lighter kite can be the difference between riding and sitting on the beach drinking beer (okay, that's not always bad).

Learning to jump: Less weight = easier to handle in the air = more confidence trying new things.

Traveling: Lighter gear means easier luggage, potentially avoiding overweight fees.

Frequent riding: If you're out 3-4 times a week, the handling improvements add up.

When to save your money:

You're just starting out (you'll crash a lot, standard materials handle abuse better).

You ride occasionally in moderate winds (the benefits won't be that noticeable).

You're on a budget (better to get two standard kites for different wind ranges than one fancy kite).

3. Why do kites look so different?

Walk down any beach on a windy day and you'll see kites of all shapes and sizes. Long and skinny ones, short and fat ones, aggressive-looking Cs, friendly-looking deltas. They're not just styled differently, they actually behave completely differently.

3.1 Understanding aspect ratio

Aspect ratio (AR) used to make my eyes glaze over. Then someone explained it simply: it's just how long and skinny vs. short and fat your kite is.

High AR kites = Long and skinny, like a glider wing.

Low AR kites = Short and fat, like a chunky cloud.

Medium AR kites = Somewhere in between (where most kites live).

But what does this actually do to how your kite flies?

High aspect: The thoroughbred

These are the kites with stretched-out, elegant lines. Think racing foil kites or big-air LEI kites with long, narrow tips.

What they do well:

Fly further forward in the wind window.

Cut upwind like a hot knife through butter.

Generate massive lift and hangtime.

Efficient power generation.

The trade-offs:

Can be twitchy and less forgiving.

Slower, wider turning arcs (not super pivoty).

Stability can suffer if you fly them too slowly.

Tougher to relaunch (long thin wingtips don't want to roll over easily).

You have to actively fly them, they won't babysit you.

Who needs high AR: Big air junkies chasing 20-meter jumps, racing fanatics going around buoys, anyone who wants maximum upwind performance and is willing to put in the skill to handle it.

Low aspect: The reliable friend

These are rounder, curvier kites with a generous middle and shorter wingspan. Most wave kites and beginner kites fall here.

What they do well:

Super stable and predictable.

Sit deeper in the wind window (steady pull).

Quick, pivoty turning.

Relaunch effortlessly.

Drift down waves without nosediving.

Stay flying even when lines go a bit slack.

The trade-offs:

Less extreme hangtime.

Don't go upwind as efficiently.

Top out sooner when overpowered.

Less speed and lift than high AR.

Who needs low AR: Wave riders slashing faces, beginners learning the ropes, foilers who want stability, anyone who values predictability and easy relaunch over extreme performance.

Medium AR: The goldilocks zone

Most freeride kites fall here, they try to blend the best of both worlds. Decent upwind, decent stability, decent everything. They won't excel at any one thing, but they'll do most things pretty well.

The rule of thumb: Higher AR = higher performance but higher skill needed. Lower AR = user-friendly and stable but less extreme.

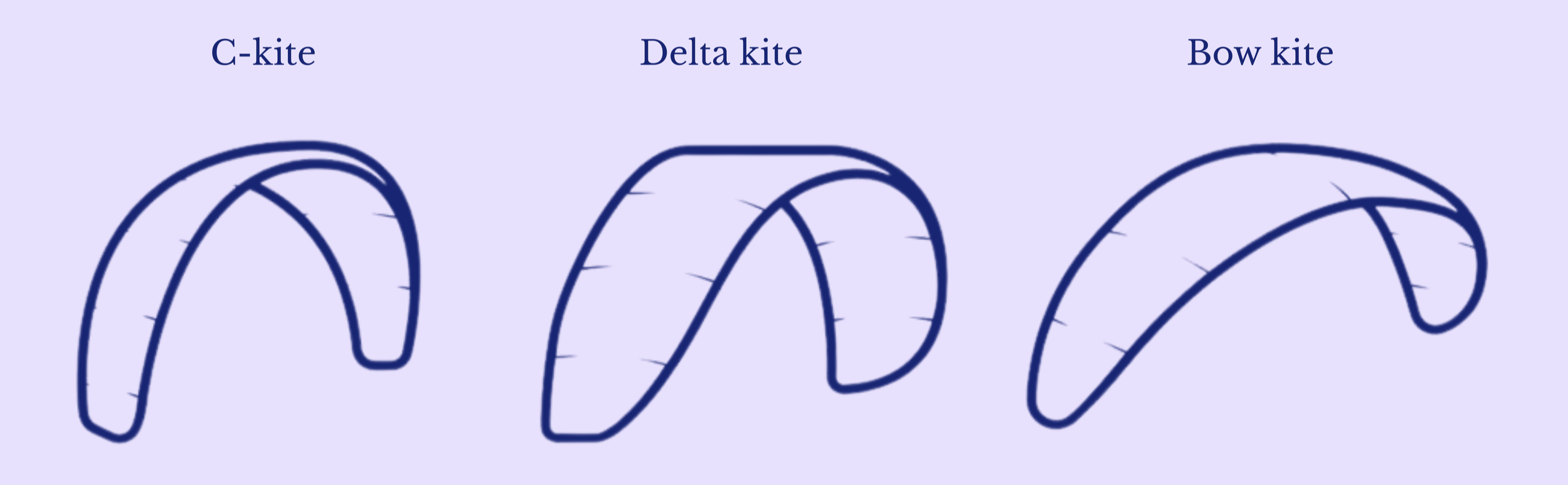

3.2 The shape wars: C vs delta vs bow

Now let's talk about the overall kite shapes. This is where things get spicy because kiteboarders have opinions about their preferred shapes.

C-kites

C-kites are shaped like a "C" when you look at them edge-on, hence the name. Square-ish wingtips, minimal or no bridles, aggressive looking.

The good stuff:

Direct, connected feel (what you do on the bar, the kite does immediately).

Consistent, predictable pull.

Slack lines beautifully for unhooked tricks.

Loop with less yank (they "catch" through the loop instead of trying to murder you).

The not-so-good stuff:

Least depower of any kite shape (even trimmed out, they're pulling).

Crappy relaunch without a 5th line (you'll be swimming).

Narrow wind range.

Unforgiving for mistakes.

Who needs C-kites: Wakestyle and freestyle riders throwing handlepasses, old-school riders who learned on these and refuse to switch, anyone who wants that raw, direct feeling.

Example: Duotone Vegas, a pure C that hardcore riders swear by and beginners swear at.

Delta kites

Delta kites have swept-back wingtips, like a triangle or delta wing shape.

The good stuff:

Stupid-easy relaunch (seriously, they want to relaunch).

Stable and predictable.

Good low-end power.

Forgiving of mistakes.

The not-so-good stuff:

Can have less top-end range.

Sometimes too much pull for the size.

Turning can be slower in bigger sizes.

Less exciting for advanced tricks.

Who needs delta kites: Beginners (these are training wheels in the best way), wave riders who need reliability, anyone who values easy relaunch over ultimate performance.

Example: F-One Bandit (especially earlier versions) popularized this shape.

Bow kites

Around the mid-2000s, bow kites changed everything. They have a flatter arc and bridled design that allows nearly 100% depower.

The good stuff:

Massive wind range (one kite covers way more conditions).

Insane depower (sheet out and it practically falls from the sky).

Excellent relaunch.

Made kiting way safer and more accessible.

The not-so-good stuff:

Historically had a mushier, less direct feel.

Bar pressure could be high.

Not as crisp for advanced tricks.

Legacy: Pure bow kites aren't that common anymore, the design evolved into modern hybrids. But the bow concept (bridles + flat arc = depower) lives on in basically every modern kite.

Hybrid kites

This describes most modern freeride kites, they blend C, bow, and sometimes delta features into one package.

The goal: Get solid depower and easy handling from the bow/delta side, plus some punchy feel and looping ability from the C side.

The result: Kites that do everything pretty well without being extreme in any direction. They won't slack lines like a pure C for wakestyle, or depower as completely as a pure bow, but honestly? Most riders won't notice or care because they're designed to handle 90% of what we actually do.

Examples: Duotone Evo, Cabrinha Switchblade, North Orbit, Core XR, basically all the popular freeride kites.

Open-c and other marketing names

You'll also hear terms like "Open-C," "Swept-C," or "SLE" (Supported Leading Edge). These are basically hybrids that lean more toward the C-kite feel but with some bridles for easier handling.

Cut through the BS: If it has bridles and isn't super aggressive, it's a hybrid. The specific name is mostly branding.

Bottom line:

Want to throw handlepasses unhooked? → Pure C

Learning or want maximum ease? → Delta/Bow-ish hybrid

Riding waves? → Delta-ish or C-hybrid with good drift

Everything else? → Modern hybrid freeride kite

Don't overthink it. Try different shapes when you can, see what feels good, and go with that.

4. Pump-up or foil: Which one should I actually get?

Okay, real talk time. Should you go with a traditional pump-up (LEI) kite or a foil? This is like asking whether you should drive a truck or a sports car, it depends entirely on what you're doing.

Let me break down both sides honestly, including where each one will make you happy and where each one will make you want to throw it in a dumpster.

4.1 Head-to-head: The real differences

Let me compare them on the things that actually matter when you're on the water:

4.2 Who actually uses what (and why)

Let me paint you some real-world scenarios:

Freeriders (like me, most of the time): 99% inflatable. The versatility and ease of use is unbeatable. Plus, nothing says "I'm going kiting" like wrestling with a pump on the beach.

Wave riders: Inflatable, specifically surf/drift-oriented ones. When a wave eats your kite, you want that quick relaunch. Trust me on this.

Big air riders: Inflatable all day. Those massive boosts and megaloops? Not happening on a foil kite anytime soon. Foils loop too slow for the big air game.

Hydrofoil racers: Foils, foils, foils. When everyone else is on the beach saying "not enough wind," foil kite riders are out there flying.

Light wind warriors: Foil kites shine here. If you live somewhere with light, steady wind, a foil kite + hydrofoil board combo will have you riding when tube kite riders are reading books.

Snowkiters: Many prefer foils. No pumping in freezing temps, incredible efficiency, pack small for hiking into the backcountry.

Travelers: Mixed bag. Foils pack way smaller (huge for airline luggage), but then you need space and wind to launch them. LEI kites are more versatile at the destination.

Beginners: Usually start on inflatables. More forgiving, easier to manage. Though some people do learn on foils (especially on land/snow).

4.3 Can you have both?

Short answer: Yes, and many riders do.

If you're building a quiver:

Start with 2-3 inflatable kites in different sizes.

Add a foil later if you find yourself sitting on the beach in light wind often.

Or if you get into hydrofoiling and want that efficiency.

My honest recommendation for most riders: Start with inflatables. Learn the fundamentals, progress your riding, figure out what conditions you ride most. Then, if light wind becomes a limiting factor, consider adding a foil.

5. Do I need 5 lines or am I overthinking this?

Okay, pop quiz: look at a kite in the sky and count the lines going to it. Got four? That's normal. Got five? Someone's either doing something specialized or clinging to the old ways.

5.1 The 4-line standard

Modern kites run on four lines: two front lines for power, two back lines for steering. Simple, elegant, works great.

How it works:

Pull the bar in (sheet in) → kite pulls harder

Push the bar out (sheet out) → kite depowers

Pull left side of bar → kite turns left

Pull right side → kite turns right

Emergency? Hit the quick release and the kite flags out on a single front line, killing most of the power

The beauty of 4-line systems is simplicity. Fewer lines = less to tangle, less to set up wrong, less to think about when you're actually riding.

Modern bridles make it work: Today's bridles (those lines connecting the kite to your lines) can be short for a direct feel or long with pulleys for maximum depower. You get tons of options without needing extra lines.

5.2 The 5-line mystery

5-line kites add a center line running to the middle of the leading edge. This extra line usually carries some tension while riding and helps the kite keep its shape.

What it actually does:

Provides center support for the leading edge

Helps prevent "bowtie" inversions (kite folding inside-out)

Makes relaunch easier (you can pull it to flip the kite)

In an emergency release, it kills power instantly by folding the kite like a taco

Why it exists: Back in the day, pure C-kites had no bridles and were stubborn to relaunch. That 5th line became the solution, it gave you a way to manipulate the kite from the water.

5.3 Who actually needs 5 lines?

Freestyle/wakestyle riders on pure C-kites: These are the handlepass-throwing, boot-wearing riders doing unhooked tricks. They want that pure, consistent pull of a C-kite, and the 5th line is their safety net (literally) for stability and relaunch.

Example: Duotone Vegas riders often use 5-line setups.

Most of us? Nope. For freeride, waves, jumping, and pretty much everything else, 4-line kites do the job perfectly. Modern designs relaunch so easily that the 5th line advantage disappeared.

5.4 The complexity factor

Here's why most people avoid 5-line setups:

Setup precision: Line lengths must be perfect. If that 5th line is even slightly off, the kite flies weird.

Tangling potential: More lines = more ways to screw up the setup. Ever tried unknotting five tangled lines in gusty wind? Not fun.

Bar compatibility: You need a 5-line bar, which limits your options.

Learning curve: There's just more to think about and more ways to mess it up.

With 4-line setups, I can swap kites easily, the setup is foolproof (mostly), and I've got one less thing to troubleshoot when something feels off.

6. What's all this brand innovation actually about?

Every year, kite brands release new models with new tech and new names that sound like they were invented by the same people who name paint colors. "Trinity TX." "Concept Blue." "N-Weave." Some of this stuff is genuinely innovative. Some is marketing.

6.1 Big players and their innovations

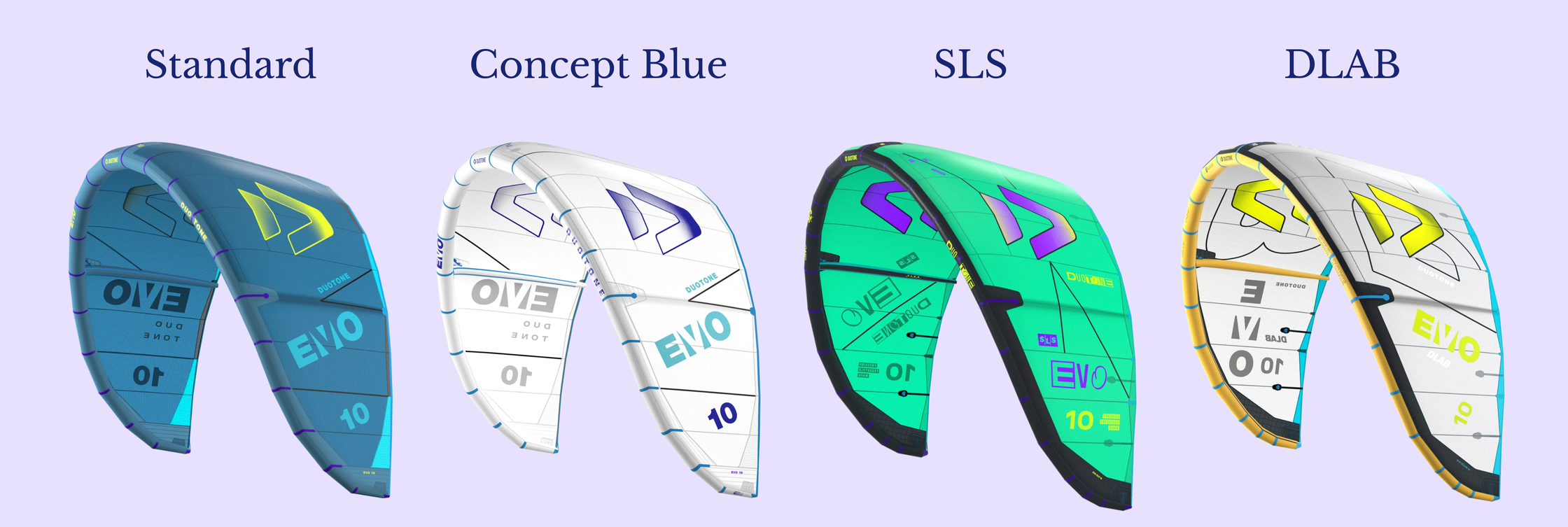

Duotone: The 800-pound gorilla

Duotone is huge. Like, if kiteboarding has an Apple, it's Duotone. And love them or hate them (usually based on their prices), they push innovation hard.

What they've done:

Trinity TX canopy: proprietary ripstop that's durable and holds shape well.

Penta TX: lighter Dacron frame material.

D/LAB line: introduced Aluula into mainstream kites, making them significantly lighter.

Click Bar: push-button line tuning (actually pretty clever).

Concept Blue: sustainability initiative aiming to cut water use ~46% and CO2 ~12%.

Their tier system:

Standard: Normal materials, normal prices (still expensive).

SLS (Strong Light Superior): Lighter tech like Penta TX.

D/LAB: No expense spared, Aluula everything, jaw-dropping prices.

The result: Kites like the Evo SLS and Rebel D/LAB that are noticeably lighter and perform better, especially in low wind and for big air.

My take: Duotone makes excellent gear. The innovation is real. But man, those prices.

F-One: French finesse

F-One is known for the Bandit, one of the longest-running kite designs ever. It's on like version 16 or something. That's staying power.

What they've done:

Popularized the delta shape (and actually patented it).

Made kites super user-friendly and easy to relaunch.

Reactor valve: big airflow pump valves for faster inflation.

Experimented with lightweight strutless designs (F-One One, a single-strut kite from years back).

Early adopters of foiling and pushed directional kiteboard design.

Recent Lite Tech materials in boards and refined canopy weaves.

Their vibe: F-One is a bit quieter than Duotone on the marketing front. They're not screaming about revolutionary tech every season, but their influence is huge, many brands followed their delta kite lead.

Airush: The tinkerers

Airush doesn't get as much hype, but they've done some genuinely clever stuff.

What they've done:

Dyneema Load Frame: ultra-strong Dyneema fibers stitched into the canopy to distribute load.

This lets them use lighter fabric without sacrificing strength.

Makes their kites ridiculously durable, tear the canopy and those fibers stop it spreading (like rebar in concrete).

Ultra-light surf kites (Airush Ultra) with minimal struts before it was trendy.

Early adopters of eco-friendly materials (recycled canopy fabric, coconut shell in boards).

My take: Airush is like that friend who quietly builds amazing things in their garage. Not flashy, but when you use their gear, you notice the thought that went into it.

North: The reboot

When the original "North Kiteboarding" became Duotone, a new company grabbed the North name in 2019. They came out hungry.

What they've done:

Orbit kite won King of the Air in its first year (huge statement).

Rock-solid stability and boosting ability.

N-Dura canopy and Ultralite bladders for weight savings.

N-Weave canopy material (lighter).

Optional high-tech frames with Aluula (Orbit Ultra).

Clever quick-release design on bars.

Experimental geo wingtip shapes.

My take: Being a rebooted brand made them innovate fast to differentiate from Duotone. They're doing well, especially in big air.

6.2 What innovations actually matter to you

Here's the real question: does all this tech make a difference when you're on the water?

You'll actually feel:

Weight reduction (lighter kites = better low wind, easier handling).

Improved depower range (means one kite covers more conditions).

Better relaunch designs (less swimming).

Bar improvements (easier adjustments, better feel).

You probably won't notice:

Specific fabric brand names (Trinity TX vs N-Weave vs whatever).

Small percentage gains in strength-to-weight.

Most marketing buzzwords.

You're paying extra for:

Aluula and exotic materials (real performance gain, real price jump).

Tier systems (SLS, D/LAB, Ultra, Pro versions).

Latest year's model vs last year (usually minimal difference).

My advice: Don't get caught up in having the latest tech unless there's a specific problem you're solving (like "I need lighter kites for light wind"). Last year's standard material kite will still work great. Save money for more sessions.

7. What's coming next?

Wondering what's on the horizon? Kite tech is evolving fast, and some of the stuff being tested is genuinely sci-fi. Here's what's coming (or already here in limited ways):

7.1 Lighter, faster, higher

The weight reduction race isn't slowing down. We're seeing:

More Aluula everywhere: What was exotic three years ago is becoming mainstream. Expect more mid-range kites with Aluula options, not just top-tier models.

Even crazier materials: Brands are testing graphene-infused fabrics, ultra-high modulus PE fibers, and materials borrowed from aerospace. A 12m kite that feels like a 9m in the air? We're almost there.

The goal: Imagine kites that perform in a bigger wind range, feel more responsive, and pack lighter for travel. That's where we're heading.

The trade-off: Prices. A used car vs. a kite is becoming a real comparison.

7.2 Frame and canopy tech

What designers are playing with:

Structured canopies that hold shape without heavy material.

Liquid-coated fibers or internal buttresses to reduce flutter.

Higher pressure systems (pushing beyond 6-8 PSI).

Segmented leading edges (different stiffness zones).

Dynamic frames that flex when needed, stiffen when they don't.

Already happening: Some kites use varying Dacron weights across the leading edge with a stiff center, softer wingtips for twist. The next step is making this more sophisticated.

7.3 The foil kite renaissance

As materials improve, foil kites are making a comeback and better than before.

Modern closed-cell foils:

Easier to handle.

Actually relaunch from water reliably (newer models).

With lighter fabrics, a 21m foil feels manageable.

Crossover potential: We might see foil tech bleed into inflatable kites, like double-surface profiles on LEIs for extra efficiency. Some prototypes already have small foil chambers under the canopy for lift.

7.4 Sustainability & longevity

"Eco-friendly" is moving from buzzword to actual priority.

What's coming:

More recycled polyester canopies.

Plant-based materials (maybe even biodegradable bladders one day).

Better UV coatings and resin treatments for longevity.

Designs that last 5+ years of heavy use.

The challenge: Making gear more durable is bad for sales but good for riders and the planet. We'll see which brands commit to this.

My hope: Kites that I can repair easily, last longer, and eventually recycle properly. That'd be worth paying more for.

7.5 What this means for us riders

More choices, more performance, more temptation to constantly upgrade.

But here's the thing: even with all this innovation, a decade-old kite still works. You're still out there dancing with the wind, and that experience transcends tech trends.

The future's bright (and probably neon orange). Whether you're flying a cutting-edge carbon-infused wonder kite or a trusty patched-up friend, the stoke is the same.

8. So... which kite should I actually buy?

Alright, we've covered a lot. Like, a LOT. Your brain might be swimming with aspect ratios, materials, shapes, and line systems. So let's bring it back to the practical question: what kite should you actually get?

8.1 Match kite to your riding style

Forget the hype for a second. What do you actually want to do on the water?

Freeride

What you need:

Medium aspect ratio.

Hybrid shape (modern freeride design).

Good depower range.

Easy relaunch.

Standard materials are fine unless you're in light wind often.

Examples: Duotone Evo, Cabrinha Switchblade, North Orbit, Core XR, F-One Bandit

Wave riding

What you need:

Low to medium aspect ratio.

Delta or C-hybrid shape with good drift.

Usually 3-strut or no-strut designs (lighter).

Easy relaunch (you'll be dropping it a lot).

Excellent drift characteristics.

Why: When you're focused on the wave, you want a kite that just sits there and doesn't demand attention.

Big Air

What you need:

Medium to high aspect ratio.

Strong, stable construction.

Good boost and hangtime.

Solid performance in powered loops.

Often benefits from lighter materials (Aluula).

Examples: Duotone Rebel, North Orbit, Ozone Edge.

Real talk: Big air kites are specialist tools. If you're not regularly going for 15+ meter jumps, a good freeride kite will boost you plenty.

Freestyle/Wakestyle

What you need:

C-kite shape (pure or open-C).

Good slack line characteristics.

Consistent pull.

Often 5-line setup for pure C-kites.

Predictable loop behavior.

Examples: Duotone Vegas, North Pulse

Foiling

What you need:

Low to medium aspect ratio.

Stable, predictable power.

Good low-end (you don't need much power when foiling).

Excellent drift for cruising.

For light wind: consider foil kites.

Why: Foiling is smooth and controlled. You want a kite that matches that energy.

Learning

What you need:

Delta or bow-hybrid shape.

Massive depower range.

Incredibly easy relaunch.

Forgiving handling.

Standard materials (you'll crash it).

Probably 9-12m for most winds.

Examples: F-One Bandit, Cabrinha Switchblade, Core XR

Critical: Don't start with a high-performance or pure C-kite. You want training wheels, not a race bike.

8.2 Budget vs performance

Let's talk money, because kites aren't cheap.

New standard material kite: €1,200-1,600

New high-tech kite (Aluula, etc.): €1,800-2,500+

Used kite (2-3 years old): €500-900

Used kite (5+ years old): €300-500

When to invest in high-tech:

You ride 3-4+ times a week.

Light wind is your limiting factor.

You're traveling frequently (weight matters).

You've got specific performance goals (racing, big air).

You can afford it without stress.

When standard is fine:

You're learning or progressing.

You ride occasionally.

You ride in moderate to strong winds.

Budget is limited.

You want a backup kite.

The used kite game, look for:

No major canopy damage (small tears are repairable).

Bladders that hold air.

Leading edge not too soft (Dacron wears out eventually).

Bridles in good shape.

A 2-3 year old used kite from a good brand is often a better buy than a new budget brand kite.

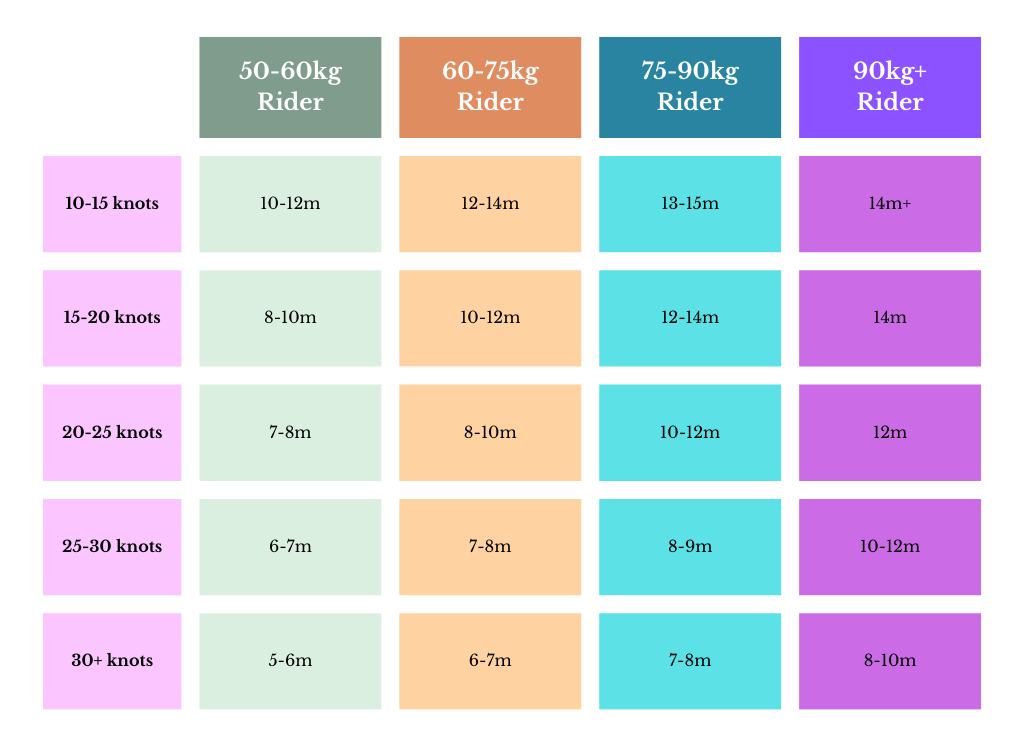

8.3 Which size to take

Most riders eventually end up with multiple kites for different conditions.

My current quiver:

6m (strong wind)

8m (everyday workhorse)

10m (light-to-moderate wind)

8.4 My honest buying advice

Start with:

Figure out your most common wind range.

Buy ONE good used kite in that size.

Learn on it for a season.

Then buy your second kite based on what conditions you missed.

Avoid:

Buying your dream quiver without testing all at once (waste of money, you'll learn what you actually need).

Buying the latest model year (last year's is nearly identical and way cheaper).

Buying multiple cheap kites instead of one good one.

Getting a C-kite as your first kite (please don't).

Do consider:

Demo days at schools/shops (try before you buy).

Previous year models on sale (huge savings).

Buying from riders upgrading (they maintain gear well usually).

Quality over quantity.

8.5 The bottom line

The best kite is the one that:

Matches your riding style.

Fits your local conditions.

Fits your skill level.

You can actually afford.

Makes you want to go riding.

Don't overthink it. Seriously. I spent weeks researching my first "proper" kite purchase, then realized after a season that most modern freeride kites from reputable brands are excellent.

The only wrong kite is the one you don't fly

So here we are. Thousands of words about tubes, bladders, aspect ratios, materials, shapes, lines, and brands. If your head is spinning a bit, that's normal. There's a lot to learn about kites.

But here's what I've learned after all this time researching, testing, crashing, and flying: the technical stuff matters, but not as much as you think.

What actually matters

Time on the water. You'll learn more from one session than from reading ten guides (sorry, I know you just read this whole thing). Feel how the kite responds. Learn its personality. Crash it and relaunch it. That's where understanding really happens.

Local conditions. The "best" kite in the world is useless if it's wrong for your spot. A high-performance race kite is amazing in steady coastal wind but terrible in gusty inland conditions. Know your home break.

Your progression. The kite that's perfect for you right now might not be perfect in six months. That's okay. We all evolve. I've sold kites that I loved but outgrew. I've bought kites I thought I wanted and realized they didn't match my riding. It's all part of the journey.

Fun. The gear matters, but not as much as the grin on your face when you stick a new trick, catch a perfect wave, or just cruise along in perfect conditions. I've had sessions on basic kites that were pure magic, and sessions on premium gear that were meh because the conditions weren't right or my head wasn't in it.

So take what's useful from this guide, ignore the rest, and go fly your kite.

See you out there.

xox Berito